Rising Inflation, How Worried Should We Be?

Dr. Sung Won Sohn

After more than 40 years of slowing, inflation has become one of the biggest concerns facing the economy. But is it too late to close the barn door? This is the key question.

Inflation is something to be concerned about for number of reasons, including unpredictability. Businesses are less likely to hire people and invest if the inflation outlook is uncertain. Higher interest rates raise borrowing costs and hurt stock and bond prices. Inflation pushes us into higher income tax brackets (only partially indexed), increasing the real tax burden for individuals and businesses.

Another problem is that many benefits from Social Security, pensions and nutrition assistance programs are indexed to inflation, but workers’ wages are not. Wages adjusted for inflation have been trending down. Inflation forces income redistribution from creditors to debtors, which encourages borrowing and increases risks in the economy.

Some believe recent price increases are temporary, and there is not much to worry about. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell has said he is confident that the current surge in inflation is transitory, and the rate will decline.

The Federal Reserve’s primary responsibility is to control inflation. The central bank’s inflation target is 2 percent over time. Why does it prefer 2 percent instead of zero? Zero is too close to deflation during which prices continue to fall.

Japan and some European countries discovered that once prices start to fall, it’s hard to reverse the trend. Why would you buy anything today — unless you need it now — if prices are expected to be lower tomorrow?

Spending and employment suffer with deflation, and interest rates can even be negative. In Denmark, a homeowner with a mortgage receives a check from the bank each month to account for the negative interest rate.

When the economy reopened after the COVID-19 pandemic, demand for goods and services surged, but widespread shortages of supplies and labor have put businesses in the position of being unable to meet the spike in demand.

The disparity has contributed to recent price hikes, but as more people return to work and supply shortages ease, there’s optimism that inflation will subside. Unfortunately, the central bank’s inflation forecast so far this year has been wide of the mark, demonstrating that no one is very good at predicting it.

How worried should we be about inflation? The headline inflation rate — or the CPI for an urban family of four — may have peaked, but don’t expect it to revert back to the 2 percent anytime soon. Supply bottlenecks continue to pop up here and there. Wages and salaries are marching upward as businesses scrambling for workers offer higher pay, bonuses and other benefits.

Businesses have no problem hiking prices. Chipotle found “no resistance” to higher prices, according to Chief Financial Officer Jack Hartung. Consumer product firms such as Proctor & Gamble and Colgate-Palmolive Co. also have raised prices with little protest from buyers.

Thanks to the largess of Washington, American consumers have money to spend. Job opportunities have improved, paychecks are getting fatter and savings have jumped. According to the latest survey by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, consumers’ inflation expectations are at a record high. We could be witnessing the beginning of a price-wage spiral — price increases as a result of higher wages.

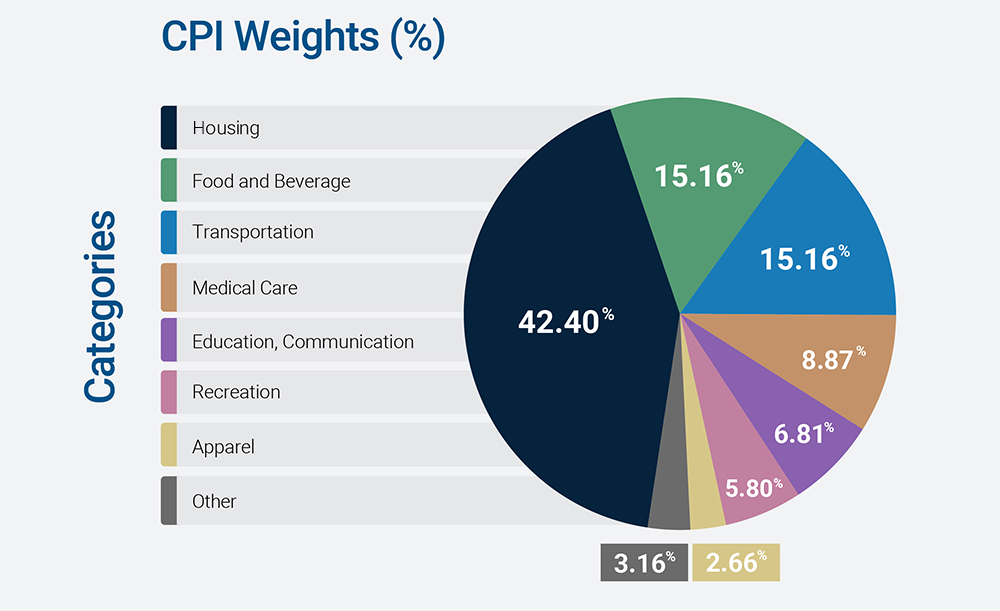

Rents, which account for about a third — 42.4 percent if energy use is included — of the consumer price index (CPI), have become a major concern (see chart). The index assumes that homeowners lease houses from themselves based on the market rent. Leases are usually renewed annually. A year ago, during the pandemic, rents fell. Now those leases are up for renewal and rents are rising significantly in the midst of housing shortages. According to RealPage Inc., rents have soared 14.6 percent from a year ago, and this could be just the beginning of more rent increases to come.

Money supply is a key determinant of long-term inflation. The late Nobel laureate Milton Friedman’s work showed that the money supply created today will cause inflation 18 months to two years later. In other words, there is a lead-lag relationship between money supply and inflation. If you act after inflation becomes a problem, it is too late.

Until recently, Powell and his predecessors followed this theory and reduced liquidity at the first hint of oncoming inflation. The taper tantrum in 2013 when, then-Federal Reserve Chairwoman Janet Yellen, started to mop up liquidity for fear of future inflation was an example. Interest rates shot up. Fortunately, the feared inflation never came.

Now Powell and his colleagues have decided to reverse the process and wait for inflation to show up before doing something about it. Furthermore, the concept of “average” inflation was introduced meaning that what matters is the inflation rate of 2 percent over time; a short-term inflation rate of 2 percent or higher can be tolerated as long as it averages out to 2 percent over time. If Powell’s modus operandi is wrong, it could lead to a higher inflation rate.

So, what has been happening to money supply? Money supply (M2) has been growing at an unprecedented rate. The Federal Reserve has financed much of the budget deficit by printing money. It purchased 76 percent of all the federal debt issued during the pandemic, holds 34 percent of all publicly held federal debt and 35 percent of all federally insured mortgage-backed securities. If Friedman’s theory is right, the massive increase in money supply should be worrisome.

In addition, there are long-term factors such as the aging labor force that point to higher inflation. In most advanced economies, including the United States, the population is getting older and the working-age population is no longer growing. The fertility rate in many countries is falling — in Korea, a university is even teaching young people how to date and fall in love to help solve the problem.

The labor force’s slow growth — or an actual fall — could lead to higher labor costs. The pandemic may reinforce the rising trend in labor costs. Workers have options and can afford to wait for better-paying jobs.

The Delta variant of the coronavirus remains a wildcard. It could ignite another round of shortages prompting higher prices. While another full-scale economic shutdown is highly unlikely, the Delta variant could reduce the availability of labor further and worsen supply bottlenecks. Asia has been particularly hard hit by the Delta variant disrupting the supply chain with shortages of everything from steel to semiconductors leading to higher prices.

Will the horse return on its own? We will have to wait and see.

###

Dr. Sung Won Sohn is a noted economist and a member of the Western Alliance Bancorporation Board of Directors. He is currently Professor of Finance and Economics at Loyola Marymount University and President of SS Economics, a consulting firm.

Bank of Nevada

Bank of Nevada, a division of Western Alliance Bank, Member FDIC, delivers relationship banking that puts clients at the center of everything. Founded in 1994, Bank of Nevada offers a full spectrum of tailored commercial banking solutions delivered with outstanding service. With offices in Las Vegas, Henderson, North Las Vegas and Mesquite, Bank of Nevada is part of Western Alliance Bancorporation, which has more than $85 billion in assets. Major accolades include being ranked as a top U.S. bank in 2024 by American Banker and Bank Director. As a regional bank with significant national capabilities, Bank of Nevada delivers the reach, resources and local market expertise that make a difference for customers.